Gabrielle B. Carusello[1]

It’s no secret that Uber Technologies, Inc. has been experiencing hardship in the news for the majority of 2016 and the hits just keep on coming. Uber has experienced unrelenting exposure in the media, with reports of a high-profile public boycott, sexism at the company, the use of secret software to elude law enforcement, and the leaked video showing Uber’s CEO Travis Kalanick arguing with an Uber driver.[2] But, the 70 billion dollar company may not be able to make it out of its latest public embarrassment.[3] One reporter predicts that this lawsuit against Uber, filed in the Northern District of California, by Waymo LLC (an entity of Alphabet Inc., parent company of Google) “is poised to be among the biggest legal fights over intellectual property so far this century.”[4]

WAYMO FIGHTS FOR ITS RIGHT TO DRIVE OUT THE COMPETITION

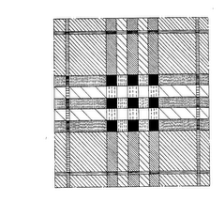

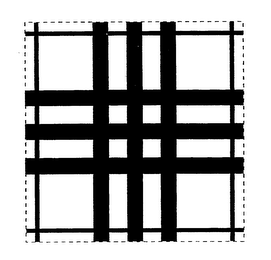

Waymo, a name given to Google’s self-driving car project, uses LiDAR as part of its self-driving technology. LiDAR, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging, is a “remote sensing method used to examine the surface of the Earth.”[5] Waymo LLC learned that Uber was also using LiDAR technology for its self-driving car project when a LiDAR vendor for both Waymo and Uber accidentally copied Waymo on an e-mail. That e-mail included attachments of machine drawings of an Uber LiDAR circuit board.[6] (Pro-Tip: please double-check your e-mail before sending confidential information!)

On February 23, 2017, Waymo LLC filed suit against Uber in the Northern District Court of California for “trade secret misappropriation, patent infringement, and unfair competition relating to Waymo’s self-driving car technology.”[7] In its complaint, Waymo alleged that the “circuit board bears a striking resemblance to Waymo’s own highly confidential and proprietary design and reflects Waymo trade secrets.”[8] If Waymo’s allegations against the defendants, Uber Technologies, Ottomotto LLC, and Otto Trucking LLC are further developed in court and are true, these companies could be liable for breaking not only federal and state civil laws, but federal criminal laws as well.

Anthony Levandowski, a former Google manager who worked on the Waymo self-driving car project, is at the center of the Waymo v. Uber lawsuit. Waymo accused Levandowski of downloading more than 14,000 highly confidential documents containing self-driving technology, said to be proprietary, from the Google servers and used the misappropriated information to start his own company, Otto Trucking.[9] It is alleged that two months after these documents were taken, Levandowski resigned without notice.[10] Further, it is alleged that a number of Waymo employees “subsequently also left to join Anthony Levandowski’s new business, downloading additional Waymo trade secrets in the days and hours prior to their departure.”[11] In addition, the information included Waymo’s “confidential supplier lists, manufacturing details and statements of work with highly technical information, all of which reflected the results of Waymo’s months-long, resource-intensive research into suppliers for highly specialized LiDAR sensor components.”[12] Waymo further alleges that, coincidentally, in August 2016, Uber bought Otto for $680 million and hired Levandowski onto Uber’s self-driving team.[13]

COPYING MAY BE SINCERE FLATTERY, BUT IS NOT ALWAYS APPRECIATED

The terms “misappropriation” and “trade secret,” which are referred to throughout the Waymo v. Uber controversy, relate to a property right recognized by common law and federal law.

The U.S. Code provides:

(a) Whoever, with intent to convert a trade secret, that is related to a product or service used in or intended for use in interstate or foreign commerce, to the economic benefit of anyone other than the owner thereof, and intending or knowing that the offense will, injure any owner of that trade secret, knowingly— (1) steals, or without authorization appropriates takes, carries away, or conceals, or by fraud, artifice, or deception obtains such information; (2) without authorization copies, duplicates, sketches, draws, photographs, downloads, uploads, alters, destroys, photocopies, replicates, transmits, delivers, sends, mails, communicates, or conveys such information; (3) receives, buys, or possesses such information, knowing the same to have been stolen or appropriated, obtained, or converted without authorization; (4) attempts to commit any offense described in paragraphs (1) through (3); or (5) conspires with one or more other persons to commit any offense described in paragraphs (1) through (3), and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, shall, except as provided in subsection (b), be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both.[14]

On the state level, California has adopted the United States Uniform Trade Secrets Act[15] under California Civil Code section 3426.1, which has been invoked in the Waymo case. Of particular interest is the definition of trade secrets:

information, including a formula, pattern, compilation, program, device, method, technique, or process that: (i) derives independent economic value, actual or potential, from not being generally known to the public or to other persons who can obtain economic value from its disclosure or use, and (ii) is the subject of efforts that are reasonable under the circumstances to maintain its secrecy.[16]

For comparison, New York takes a different approach when it comes to trade secret protection. As one court has broadly stated, a trade secret is any:

formula, pattern, device or compilation of information which is used in one’s business, and which gives [the employer] an opportunity to obtain an advantage over competitors who do not know or use it.[17]

The body of law outlined above provides insight as to what legal provisions for misappropriation of trade secrets may be applied. However, in trade secret cases, rarely can one prove misappropriation by direct evidence and one must often draw inferences and rely upon the overall weight of circumstantial evidence. If Waymo is able to provide convincing evidence that its private documents were applied to Uber’s circuit boards as the basis of Uber’s self-driving unit, then Uber may be in trouble at both the federal and state level.

PRELIMINARY INJUNTION: A FIRST SIGN OF SUCCESS ON THE MERITS

Presiding at the District Court, Judge Alsup was persuaded that the evidence Waymo provided was sufficient to partially grant and partially deny a preliminary injunction against Uber.[18] In the preliminary injunction hearing, Judge Alsup stated:

[y]ou don’t get many cases where there is pretty direct proof that somebody downloaded 14,000 documents, and then left the next day.[19] Waymo has also sufficiently shown…that the 14,000-plus purloined files likely contain at least some trade secrets.[20]

Uber does not dispute the allegation that Levandowski obtained 14,000 files from Waymo, but rather Uber maintains that “Waymo’s files never crossed over into Uber’s servers or devices and that ‘Uber took strict precautions to ensure that no trade secrets belonging to a former employer would be brought to or used at Uber.’”[21] The Court stated these denials:

leave open the danger of all manner of mischief…it remains entirely possible that Uber knowingly left Levandowski free to keep that treasure trove of files as handy as he wished (so long as he kept it on his own personal devices), and that Uber willfully refused to tell Levandowski to return the treasure trove to its rightful owner. At best (and this has not been shown), Uber may have required Levandowski, as a matter of form, to commit not to use the Waymo files.[22]

On May 15, 2017, Judge Alsup partially granted Waymo’s preliminary injunction on the showing by Waymo of likely success on the merits. However, the transcript of the proceedings remains under seal until August 2017. Moreover, the Court also went so far as to refer the matter to the United States Attorney General for investigation of possible theft of trade secrets.[23] The injunction “mainly prohibits Levandowski from working on Uber’s LiDAR- a measure Uber has very recently implemented of its own initiative, so the hardship on the defendants will be minimal.”[24] The potential criminal charge did not stay the Court’s hand when deciding on the motion for preliminary injunction proceedings:

if you think for a moment that I’m going to stay my hand, because your guy [Anthony Levandowski] is taking the Fifth Amendment, and not issue a preliminary injunction to shut down what happened here, you’re wrong. This is a very serious — now, some of the things in your motion are bogus. You’ve got things in there like lists of suppliers as trade secrets. Come on. It undermines the whole thing. But there are some things in that motion that are very serious. They are genuine trade secrets. And if you don’t come in with a denial, you’re probably looking at a preliminary injunction.[25]

Further, the Court stated that Uber did not deny the allegation that trade secrets were misappropriated by Levandowski. The Court, along with Waymo, questioned whether or not Uber knew that Levandowski unlawfully took proprietary documents from the moment that Uber purchased Otto Trucking, LLC.[26] In the order, the Court states that, “Waymo has supplied a compelling evidentiary record that Levandowski resigned without prior notice from his position at Waymo under highly suspicious circumstances…”[27]

Waymo has shown “at least serious questions going to the merits as to whether Uber’s adoption of [the technology] used by Waymo resulted from old-fashioned, all-American misappropriation of trade secrets.”[28] However, the preliminary injunction was denied in part because some of the technologies that Waymo claimed to be trade secrets were deemed too general, namely “general engineering principles that are simply part of the intellectual equipment of technical employees.”[29] Nevertheless, the Court pointed out in support of the injunction:

Levandowski remains in possession of over 14,000 confidential files from Waymo, at least some of which likely contain Waymo’s trade secrets. Misuse of that treasure trove remains an ever-present danger wholly at his whim. Under these circumstances, the harm that Waymo is likely to suffer as a result of such misuse cannot be unwound after the fact, nor can it be adequately compensated for with monetary damages.[30]

While we await public disclosure of the record to understand the whole story, commentators are left to speculate.

The inevitable disclosure doctrine and laws enacted by Congress under the Economic Espionage Act, may provide an additional basis for relief on behalf of Google. While some jurisdictions follow the “inevitable disclosure doctrine,”[31] which allows a plaintiff to “prove a claim of trade secret misappropriation by demonstrating that defendant’s new employment will inevitably lead him to rely on plaintiff’s trade secrets,”[32] California does not officially follow this theory of tort. Nonetheless, under the California Uniform Trade Secrets Act (CUTSA), courts are allowed “to enjoin an employee from working for his employer’s competitors because of the threat of misappropriation.”[33] This section of CUTSA could be particularly useful to Waymo since Anthony Levandowski has chosen to invoke his Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination and Waymo has been unable to search his personal laptop, or even question him about the misappropriation of Waymo’s files.[34] However, CUTSA states:

actual or threatened misappropriation may be enjoined. Upon application to the court, an injunction shall be terminated when the trade secret has ceased to exist, but the injunction may be continued for an additional period of time in order to eliminate commercial advantage that otherwise would be derived from the misappropriation.[35]

The likelihood of a permanent injunction, however, is heavily reliant on whether Waymo can provide convincing evidence at trial. Waymo will need to be able to provide evidence of irreparable harm, show the balance of harm favors Waymo, demonstrate that Waymo has a likelihood of success on the merits of the case, and establish that public interest favors the granting of a permanent injunction.[36] Should this case be investigated by the United States Attorney General in the coming weeks, the Economic Espionage Act, enacted and proscribed by the U.S. Code, could be applied to Levandowski with criminal ramifications.[37]

While in the past, it was believed that one could hide evidence of misconduct and destroy one’s paper trail by shredding documents, now with the advancement of technology and the digital age, there is also a belief that one can likewise delete files and data to hide one’s tracks. However, neither method provides a clean getaway. The District Court found a classic case of misappropriation of trade secrets with the absence of 14,000 documents, but there is plenty left to be decided in this controversy by following the electronic footprints of these documents. The outcome of this case may ultimately be determined by the additional discovery that may be brought forth by either Waymo’s lawyers or the Attorney General, and if so, it could be the end of a tumultuous ride for Uber.[38]

[1] The information contained in this article does not constitute legal advice or legal opinion, but has been prepared for general informational purposes only. Any opinions expressed in this article shall not be construed to represent the legal opinion of this firm, its attorneys or any of its clients. The receipt of this article does not create an attorney-client relationship. ©2017 Wyatt & Associates, LLP

[2] LaFrance, Adrienne, Travis Kalanick is Taking a Break from Uber, The Atlantic, June 13 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/06/everything-you-need-to-know-about-driverless-cars-a-cribsheet/518847/.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] National Ocean Service, What is LIDAR?, http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/lidar.html, (last visited July 18, 2017).

[6] See Complaint at 3, Waymo, LLC v. Uber Technologies, Inc., No. 3:17-cv-00939 (N.D. Cal. filed Feb. 23, 2017).

[7] See id at 2. (Waymo also brought claims for violation of California Business and Professional Code Section 17200).

[8] Waymo, LLC, N.D. Cal., Complaint at 3.

[9] See id.

[10] See Order Granting in Part and Denying in Part Plaintiff’s Motion for Provisional Relief at 2, Waymo, LLC v. Uber Technologies, Inc., No. 3:17-cv-00939 (N.D. Cal. filed May 15, 2017).

[11] Waymo, LLC, N.D. Cal., Complaint at 4.

[12] Id.

[13] Waymo, LLC, N.D. Cal., Order at 4.

[14] U.S.C.§ 1832 (a)(2016); see also U.S.C § 1832 (b) (“Any organization that commits any offense described in subsection (a) shall be fined not more than the greater of $5,000,000 or 3 times the value of the stolen trade secret to the organization, including expenses for research and design and other costs of reproducing the trade secret that the organization has thereby avoided”).

[15] CAL. CIV. CODE § 3426.1 (d)(1985).

[16] U.T.S.A § 1.4 (1986); see also U.T.S.A. § 1.2 (1986)…(Misappropriation is defined as “(i) the acquisition of a trade secret of another by a person who knows or has reason know that the trade secret was acquired by improper means; or (ii) disclosure or use of a trade secret of another without express or implied consent by a person who (A) used improper means to acquire knowledge of the trade secret; or (B) at the time of disclosure or use, knew or had reason to know that his knowledge of the trade secret was (I) derived from or through a person who had utilized improper means to acquire it; (II) acquired under circumstances giving rise to a duty to maintain its secrecy or limit its use; or (III) derived from or through a person who owed a duty to the person seeking relief to maintain its secrecy or limit its use; or (C) before a marital change of his [or her] position, knew or had reason to know that it was a trade secret and that knowledge of it had been acquired by accident or mistake”).

[17] Ashland Mgt. v. Janien, 82 N.Y.2d 395, 407 (1993). New York uses a six factor test to determine misappropriation of trade secrets: “1. the extent to which the information is known outside of [the] business; 2. the extent to which it is known by the employees and others involved in [the] business; 3. the extent of measures taken by [the business] to guard the secrecy of the information; 4. the value of the information to [the business] and [its] competitors; 5. the amount of effort or money expended by [the business] in developing the information; 6. the ease or difficulty with which the information could be properly acquired or duplicated by others”); See also Restatement (First) of Torts § 757 (1939).

[18] Waymo, LLC, N.D. Cal., Order at 2.

[19] See Document 63 at 20, Waymo, LLC v. Uber Technologies, Inc., No. 3:17-cv-00939 (N.D. Cal. filed Feb. 23, 2017) (Transcript of Proceedings on Thursday, March 16, 2017).

[20] Waymo, LLC, N.D. Cal., Order at 2. (Emphasis in Original).

[21] See id at 8.

[22] Id. (Emphasis in Original).

[23] See Order of Referral to United States Attorney at 1, Waymo, LLC v. Uber Technologies, Inc., C-17-00939 WHA (N.D. Cal. filed May 11, 2017).

[24] Waymo, LLC, N.D. Cal., Order at 22.

[25] See Document 131 at 7, Waymo LLC v. Uber Technologies Inc., No. 00939 (N.D. Cal. filed Feb. 23, 2017).

[26] Waymo, LLC, N.D. Cal., Order at 7.

[27] See id at 2.

[28] See id at 15.

[29] Id.

[30] See id at 20.

[31] Les Concierges Inc. v. Robeson, No. 09-1510, 2009 WL 1138561, at 2 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 26, 2009).

[32] PepsiCo, Inc. v. Redmond, 54 F.3d 1262, 1269 (7th Cir. 1995). See also Molon Motor & Coil Corp. v. Nidec Motor Corp., No. 16-cv-03545, (N.D. Ill. filed May 11, 2017).

[33] C.U.T.S.A. § 3426.2 (a)(1984).

[34] Waymo, LLC, N.D. Cal., Order at 6.

[35] C.U.T.S.A. § 3426.2 (a)(1984).

[36] Waymo, LLC, N.D. Cal., Order at 11-21.

[37] U.S.C.§ 1831 (2013); (“(a) whoever, intending or knowing that the offense will benefit any foreign government, foreign instrumentality, or foreign agent, knowingly— (1) steals, or without authorization appropriates, takes, carries away, or conceals, or by fraud, artifice, or deception obtains a trade secret; (2) without authorization copies, duplicates, sketches, draws, photographs, downloads, uploads, alters, destroys, photocopies, replicates, transmits, delivers, sends, mails, communicates, or conveys a trade secret; (3) receives, buys, or possesses a trade secret, knowing the same to have been stolen or appropriated, obtained, or converted without authorization; (4) attempts to commit any offense described in any of paragraphs (1) through (3); or (5) conspires with one or more other persons to commit any offense described in any of paragraphs (1) through (3), and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy shall [be punished], except as provided in subsection (b), be fined not more than $5,000,000 or imprisoned not more than 15 years, or both; and that any organization that commits any offense described in subsection (a) shall be fined not more than the greater of $10,000,000 or 3 times the value of the stolen trade secret to the organization, including expenses for research and design and other costs of reproducing the trade secret that the organization has thereby avoided”); see also U.S.C.§ 1831 (5)(b).

[38] For further information, or any questions regarding intellectual property law and trade secrets, you may call our firm at (212) 681-0800, or e-mail us at info@wyattip.com.

Recent Comments